![]()

Aug '03

by Mark West

I joined the cabal of

Terror Scribes after it had been going for a few years and one of the

first people that I began corresponding with was Joe. It would be a couple of years before we finally met,

face-to-face, at a gathering in Leicester - I did a reading and so did he,

“Inner Demons” from his wonderful “Love Stories Of The Undead”

collection. We got on well,

sharing several interests including cigars - it was a very smoky night, in

the end.

A year or

more later, we met up again in Birmingham, for a big genre event, where he

won a prize for his story “Seen But Not Heard” - which I voted as my

favourite story. We didn’t

get to spend a lot of time together at that gathering - it was a busy

evening, there was a fire alarm that evacuated all of us and Alison &

I had to leave early as we were off on holiday - but we did speak.

We

also discovered that Rainfall Books was going to publish a collection from

each of us the following year. And

so it was that Joe and I sat down, one dark and stormy night, in a

suitably decadent watering hole and - over an evening of fine wines and

good cigars - had a chat.

MW:

Joe, I just finished reading your collection and I was very impressed with

it. I loved "Love Stories Of The Undead", but the stories

here seem to be more mature and stronger. Was there a long period of

time between your writing that original collection and this one?

JMF

Not really, but the stories in this book do span a greater

stretch of time than the ones in 'Love Stories of the Undead'. The stories

in the first book were all written, pretty much, within a year. During my

mid-teens I'd got more side-tracked with my writing than I would have

liked, though I could blame this on my studies it was more due to the more

pleasant distraction of girls, and when I started up again properly I was

eager to get a collection together, so basically as soon as I'd completed

ten new stories I said 'That's it! I've got a collection!', and added to

it whilst I was writing more stories during the process of getting the

book together.

In this new book, the earliest stories were written just after I'd

finished writing my novel 'Those Left Behind', in the summer of 1999, and

the latest stories were completed at the end of last year. I feel it

represents the best of my completed short stories in that time. There were

a few that I jettisoned from my original idea of this collection, largely

because of the length of them and Rainfall wanting a shorter book. Some of

these may well make it into a future collection, though not without some

reworking.

MW:

Did you revise the stories for inclusion in the collection, or are

they as they were when you first finished them?

JMF With some exceptions, they

are the original finished product. I’ve done some minor tidying up, but

the only story which has gone through complete redrafting is ‘The Cursed

Tree’, which is a rewrite of the original version, though it ended up

nowhere near as different as I thought it might.

MW:

Just a general question (probably only for those writers amongst us), but

can you describe your normal working practises? Do you write several

drafts whole, or do you work and re-work each line as you write it?

For example, the pursuit through the woods in both "Denizen" and

"Dark Side" are very frantic and fluid - if I could write a

first draft like that, I would be overjoyed.

JMF You may well hate me for

saying this then, but I do generally go with my first-draft! I dislike

rewrites, and prefer to smooth out any rough edges as I go along. Having

said that, I do tend to get restless fairly quickly with my work as it

ages and so it's best if I can get it out there as soon as possible.

Otherwise as time goes by I'll see - like most artists of any kind - more

and more things I feel that I could improve upon.

My actual writing process is fairly straight-forward, once I know where

I'm going with the day's work, I'll set down and set to it. When things

really get moving, like the scenes you describe, it just flows magically.

I don't have a problem with those kind of scenes, they keep me hooked.

It's like going into a trance when I write, I may have music playing but

it's more to keep me going for a set length of time if my attention lags

than anything else. I'm not aware of anything except the scenes that are

playing out in my mind, and the words just flow through me onto the page.

That's the magic of the art to me.

MW: I know that every writer gets asked

"Where do you get your ideas" and, generally, doesn't like it so

I'll try and add a new spin to it. When I write, different images

seem to come from several sources and link together. Do you find

that happens and do you also find that one story could throw out a lot of

plot ideas that can be developed and explored in separate, stand-alone

stories?

JMF

For

me, my short stories are generally developed from one of the many

wonderfully strange incidents that have actually happened to me, only

played out to its worst possible degree. As I've mentioned, it's a very

subconscious process when I'm actually working so I tend not to notice or

be able to think about anything outside of the world that I'm creating at

the time. If variations on the theme do occur to me then it's most often

at a later date when I'm re-reading the work, or discussing it with

others. That actually can give me a whole new perception on something I've

written. There are times when people have seen something in my work that I

wasn't consciously aware of writing about, but I can then step back and

see was there all along.

MW: With "Coming Down" and "The

Cursed Tree", you almost seem to play around with the conventions of

horror and story-telling - as in, 'It all sounds so perfect that you can

tell it's all leading up to disaster, right?' from "The Cursed

Tree". Was this a deliberate conceit for the stories in this

collection, or is it something that you find yourself doing from time to

time - playing with the form and enjoying the act of writing?

JMF

The

fact is we all know we're reading a story so it doesn't particularly hurt

to acknowledge that in the writing. David Porter, writing in The

Literature of Terror, disliked M. R. James so much because of his knowing

references and asides, but that doesn't seem to have damaged him to many

fans, myself included. Both stories you mention are written in a

first-person narrative, which makes them less formal from the off, and

perhaps they would both have been unbearably heavy-going without such

elements. You can't fool your readers, they'll think less of you for it,

so just before you really lay on the horrors it's okay to tip them a wink,

they know something bad is coming because they're reading my story, not

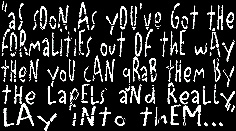

the latest Maeve Binchy. But as soon as you've done it, got the

formalities out of the way, then you can grab them by the lapels and

really lay into them.

It's certainly important to enjoy the act of writing, and not draw back

from trying out new ideas or styles within it. Quite often it's what will

get one of the rut one may have fallen into.

MW:

A good point - ‘to enjoy the act of writing’.

Do you find that the act is more enjoyable if it’s a story that

‘just comes to you’ or if you’re writing something for a specific

market in mind, ie a themed anthology?

JMF I’d have to say the

former. Trying to write for themed markets tends to stifle me and shut

down a wider flow of ideas that would otherwise be very productive.

That’s not to say I don’t welcome the invitations or indeed the

challenge. The other year I was asked to produce a tale featuring either a

female superhero or supervillian for a themed anthology, and happily

agreed, although to my shame I never actually got around to it and the

book has no doubt gone ahead by now without me. Still, the idea still

appeals to me, and resurfaces from time to time though as yet with nothing

very substantial trailing in its wake. My story ‘The Hungry Ones’

could have been my reply to an invitation into a book of tales of

subterranean dwellers if I’d written it when it first occurred to me,

and my notebooks feature fairly lengthy outlines for two different

possibilities for Brian Willis’s award-winning ‘Hideous Progeny’

anthology, neither of which I ever started work on. Stories do come alive

much easier for me when they just grow, fungus-like, somewhere in a dark

corner of my mind, but still I try.

MW: "They Are, We Were" is written from

the point of view of a 70 year old man. Bearing in mind that you're

in your twenties, was writing this character at all difficult and how did

you go about researching the rhythms and patterns of speech, as they sound

very natural and unaffected.

JMF I

find it very easy to become characters when I'm writing them, and have

most fun with the ones that are nothing at all like myself. Which is why I

feel my most vivid characters are the women, or the old men, or the kind

of people you’d have nightmares about turning into. It's always been

that way, I can distinctly recall an early attempt at a novel, I must have

been about 12 or 13 at the time, and realised I was enjoying writing from

the viewpoint of a 50-year old married man more than from the viewpoint of

a character who was a 13 year old schoolboy. My first ever published

story, around the same time, was from the viewpoint of an almost

Lovecraftian monster. I'm a great psychologist, and it's an interest of

mine, and I find that I can figure people out very quickly and quite

thoroughly, which is a useful skill to have in life, not least when one is

a writer.

MW: The majority of the stories have very well

realised locations - I'm thinking specifically of the waxworks and the

forests from "The Voice Of The Denizen" and "The Dark Side

Of The Woods". Are these all fictional or based on real areas?

JMF

All

real! I could walk you through these locations. Even worse still, many of

them are taken from real incidents. The waxworks you can find nestled

somewhere in the shadow of Blackpool tower. I can't pretend to have

visited that many such places so when I wanted to pay homage to that

staple horror location, I naturally drew upon it. That story also came

from a lot of research I was doing into ageing and - particularly -

Alzheimer's disease, for a novel I was writing. The woodland-based stories

you mention are derived from two particular incidents (one of which was

perhaps the strangest and most inexplicable thing that's happened to me),

in the real-life locations that I then set the stories in. I think it's

important to give your stories a firm base in reality, because if it

doesn't come alive for the writer then there’s a good chance it never

will for the reader either.

MW:

As you know, I think "Seen But Not Heard" is an incredible

story. Tell me how it came together, from the initial idea to the

writing of it.

JMF It came from spending a lot

of time driving all across Suffolk visiting various haunted and infamous

locations, not least the site of Borley Rectory. I wrote the first

paragraph in August 2001, and knew pretty much where I wanted to go with

the rest of the story, but actually did nothing more on it until Spring of

the following year, when I sat down and wrote the rest of the story in one

draft in a glorious complete three-hour session.

The story really came alive for me while I was writing it, and there were

fantastic times when I would just sit back from the desk with what must

have been a singularly demonic smile, rub my hands together and realise

I'd just scared myself with something I'd written. I knew the points which

really worked for me, and hopefully the readers too. I'm very proud of the

tale, and the reaction that it went on to receive.

JMF

MW:

"Coming Down" treats a very real, very unpleasant subject in a

clever, almost oblique way, using that angle to show how it affects

different people. Did you find it difficult working with the subject

of under-age porn?

JMF I didn't find it difficult

because I didn't believe I was actually doing anything all that meaningful

with the subject. For me, whilst I was writing it, the element of the

child pornography was just a nasty subtext in it, and what I was largely

doing was talking about secrets, what's really lurking behind the face of

every person you pass by on the street or even in cases your closest

friends.

I'm not sure that I could ever tackle such issues as child porn in a

serious work, that would be difficult for me simply because I wouldn't

feel qualified to do so. I'm not political and I'm not a moral crusader,

but I'm never afraid to say what I feel and it's obvious to me that things

like child abuse and child pornography are very wrong, and there's some

damaged people behind them who end up causing irreparable and lifelong

damage to the innocent victims involved. I've seen those lasting effects

close up, and there's nothing that could excuse the causes.

MW: In general, you seem to use the countryside as a location in a lot

of your stories. Do you find yourself more at home there, rather

than in an urban environment? I ask because your characters don't

seem to enjoy the great outdoors too much.

JMF

Maybe

that's some kind of justification for what happens to them! I love and

respect the countryside and I'd hate to think that these kinds of things

would happen to me whilst I was out for a nice peaceful stroll. I do feel

so much more at home in the countryside than I do in urban areas. I grew

up on the edge of a large industrial town, but loved to run away into the

woods and surrounding countryside, which just seemed like a whole

different world to me, and still does. Every home I've had of my own has

been in quiet areas and it's where I like to spend most of my free time. I

couldn't live in a large town or city and be happy. I saved the life of a

friend of mine when we were kids, and then some years later after we’d

grown apart he was shot dead on his own doorstep and the night after the

house was burned down so the police couldn’t search for evidence. It’s

times like that you tend to think maybe it’s time you left town for

somewhere a little more peaceful.

MW: If there is a theme to this collection, it

seems to me to be the idea of man destroying nature (or attempting to) and

nature fighting back (certainly, this is what I get from

"Denizen", "Dark Side" and "The Cursed

Tree". It's also a thread from your earlier stories (especially

"Not One Of Nature's Own") and your non-fiction account of an

expedition to the moors one night. Is this something that's close to

your heart?

JMF

I

have a huge respect, and awe, for the countryside, and often feel

uncomfortable in large towns and cities and crowded areas. I dealt with

some of this in a novella called 'The Man Who Killed an Angel', which was

a psychological thriller in which the main character despised and feared

the city in which he lived and the amount of contact with strangers that

it forced him into. The countryside is rejuvenating to my soul, it's

inspiring, and it's uplifting. I think there are things out there, other

forces, powers, elementals, call them what you will, that are on a totally

different level to us, that we cannot always see, or hear or even feel,

but on occasion we become aware of if you know how to be receptive to

them. It's why I find such reward in reading Blackwood. The world is

getting horribly overcrowded and I love to find places that remain largely

untouched by man, not crowded with housing estates and busy roads and the

kinds of people you wouldn't really want to have to spend time with.

That's horror to me, that's drudgery. I guess in that case the idea of

nature fighting back has a certain appeal! But just as often in my work

it's a case of the characters being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

MW:

Joe, thank you very much. Now how about some more absinthe?